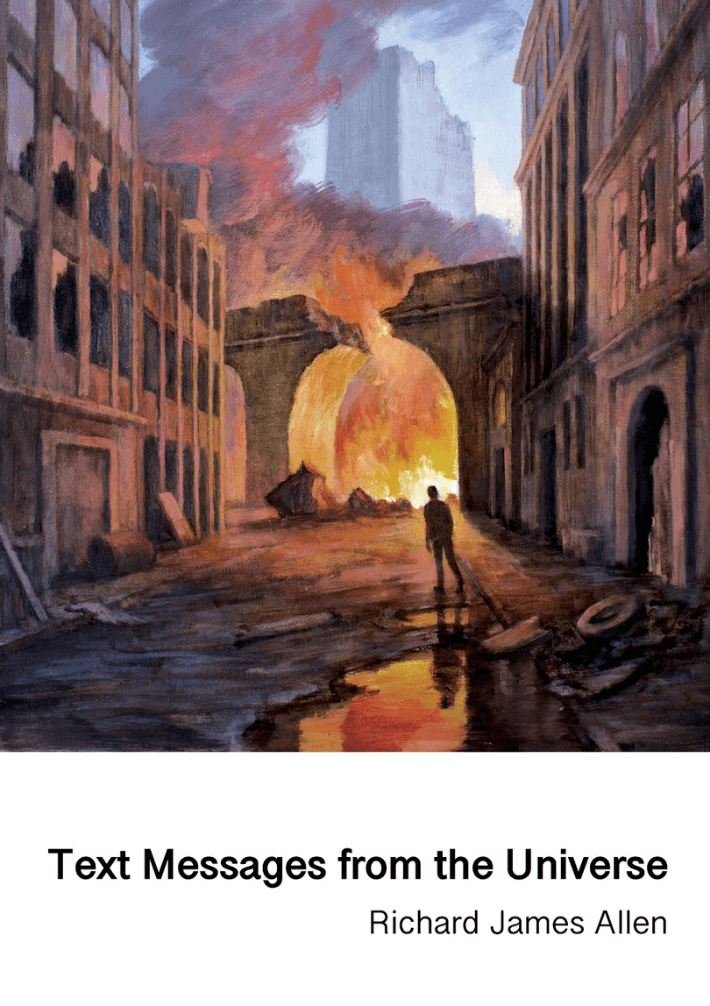

Text Messages from the Universe

Navigating the Middle Darkness with Richard James Allen

About a decade ago while living in China I would select mountainous dots on the map, at reasonable random, and with a friend or two ride the slow, green-skinned trains or the rickety buses out for hikes of approximation. This scheme rested on the usually fulfilled hope that there would yet be a path, perhaps some creaking bamboo grove, no superfluity of people: some locale that has always-been beyond the reach of convenience stores, if not Coca-Cola. Oases of inconvenience for wandering selves, salves for pattering minds.

When you stray from the tourist track in China there is little danger that even the reliably orientation-free will become truly lost (“you are always actually found” 91)—there is always some kind of path, and if you keep walking, you will always stumble down into a village (do not try this in Australia, where aimless ambling is a recipe for search and rescue, where creeks on maps may be a dust formality). No, in the clearance, you will perhaps be rewarded with some locally prized variety of tea; a lavishly rustic dinner; the old elan of foreignness, unfamiliar again, in little patches spared the new flattening dispensation. For the time being, we would eat and studiously keep clear of the pits of authenticity discourse or idyllic romanticism, we accepted the sorghum toasts and avowals, and rose early by our standards and tardy compared to everyone else.

On one such amble in the rolling countryside near Wenzhou, where even the hamlets showed symptoms of a construction boom, with ominous pictures of golf courses on local council billboards, I remember encountering for the first time something I had previously only read about, likely in some sourcebook of tradition or in a peasant anthropology of the old style: the little tomblets dedicated to the ‘hungry ghosts’ on the outskirts of villages, often with some small offerings—oranges, perhaps—and sticks of incense in an ashen urn before them. Hungry—that’s the evocative English translation, and it can claim a reasonable linguistic provenance. But ghostly starvation occurs principally when they have no descendants to feed them after death (will any of us have descendants in the goodness and fullness of time? How far can we ravenous expect the chains of descent to hold our cowering progeny?). Now that I put my mind to it, however, the characters inscribed in the tomb were not immediately about hunger: they represented the loneliness of souls 孤魂, their incommunicability, their orphan quality. They belong to a shadow family of solitary words and ideas, with multiple renderings casting light on different facets of the original: abandoned, hungry, lonely; ghosts, demons, spirits, souls. Our orphaned ancestors, the peckish shades.

Reading Richard James Allen’s new book of prose poetry, Text Messages from the Universe, I found myself brought back with power and concentration to a concern for these liminal spaces, to the question of the not fully departed, to the lingering of vanished subjects, to these sudden remonstrances by the wayside, to reflect and recollect. Halt on your way, traveller. Unusual to arrive in any text, both in the middle of the story yet also at the instant of death, “into the eyes of headlights” (5). But that is the startling entry point in the first section, ‘An Introduction to Dying: An Odd Way to be Born’, with the considerations occurring in and around the instant of dying, the fragmentation, the visceral undoing of an “unhappy meeting of textures” (5), while the second part, ‘The Book of Bad Dreams’, in forty nine text messages, is an elaboration of the intercalation, the posthumous peripatetikos, since “You are not going to die. / You are already dead” (21). While the first section is illustrated with black-and-while blurs of the city, in ‘The Book of Bad Dreams’ we are vividly accompanied in this intermediary world by dancers’ images, robes swirling and frozen, stills from screendance, webbed and ribboned, impersonal, convulsive. Is dying an art (like everything else)?

I regret to inform you that it does not look good for us, for you, for us all, since not only are “Your insides … coming out” (12), but you are “further and further from the light” (60). Who speaks? The book’s voice, perhaps a sympathetic psychopomp, or an idle god fiddling with his chess pieces, or maybe the Universe itself whispering to its eternal second person, the avaricious self. We the hapless, the undead readers, the humans slipping out of their fleshy sheaths—we require a vade mecum, require assistance disembarking, need help navigating to a shore, or figuring out how to let the boat disintegrate, instruction on how not to yearn for breath. Ironically, this attention to detail returns quietus to its proper shelf, death not killed so much as bracketed, sidelined, a skill to be learned and superseded, reduced to a vertex, without extension, repeated, a puffed-up emcee introducing cabaret numbers, “Happy, floaty, oddball little jigs” (23).

Decease here is an incident provoking a change of state, a moment of inattention that ratchets back the cycle, a game over with the compulsion to rev up the rigmarole again, a space of confusion before the lures and entrapments of humanity resume. But this liminal time ushers in opportunity: perhaps instruction, hints from the universe’s service to the people, that the chain can be sundered, the coil unsprung, that the self can disintegrate like “freshly baked bread that has been pulled apart”, so that perhaps this time the shuffling of samsara can be interrupted, the wheel sabotaged? Reflections towards a way out for a species born entombed, subject to a farcical interval of life between the two great absences, here we are on the cusp of a terrible reckoning. The real is stripped off, the “theatrical tricks of the mind” (80) exposed, the story making for once evaded: “Step off to the side of the narrative” (82). For once at the centre is the promise, the vacant embrace rather than the terror of undoing, the warmth of this “endless caress of night” (25).

But we the readers are problem children, we roam limbo uncalibrated, the change of states has encountered a hitch, we persist residually, a lostness between the worlds, a soul stuck in the wreckage of a street accident perhaps, expressed in the vocabulary of anxious modernity remaining to us, our fear of backstreets, our latching to photographs, to identity documents, “is there a lost and found office of the mind?” (44). The book could be a manual for haunting—since these days we are all buried outside the sanctified ground, at the crossroads, in little lonely wayside urns? The soul is a trapped beast, confined in a “character that you must put on, like a pair of gloves” (49), but rather than accruing fear over time as the disorientation grows, the promise of dissolution nears, flickering in and out of focus, “the way out at last” (94), perhaps . . . Keep reading, keep reciting, have hope not of heaven but of getting round the tyranny of the ego, after the dissipations of the youth, cast your mind forward to the dissipations of your energies, of your humours.

Limbo, Latin, a border; bardo, Tibetan the interval between. In the book’s bio, Allen directs us to what is known in English as The Tibetan Book of the Dead, unstable and inspiring artefact of faith and hopeful translation, and its discourse of the antarābhava, the bardo, what I know from Chinese as 中有 “what exists in the middle” or 中陰 “the middle darkness”, or even “the middle dankness.” But although this interval of being shares the spirit of preparation and forbearance of Catholic grisly memento mori, we are not headed for the boredom of contrapuntal angel choirs or the Christian God’s sadistic eternal hell flames, nor even to await in prayerful purgatory some buyout or term of limitations. Neither is hell merely in other people, hell is more insidious and pervasive, the flames are ongoing and in oneself, a low-intensity, mostly subconscious bondage, hell as self, the puling ego. Thus, in Messages we begin with the afterpains of life, the screechingly similar hurl into death, the inevitable sense of unfinishedness, of desperate longing for the prison, to tie things up, to tie oneself back up. But here are the words to release, to shuffle offstage. The groping out of the liminal space, the purgatory or the prenatal sac is something promised in every religion, the humans recently divested of or shifting hopelessly towards another identity. In the meantime, in 49 messages from ‘the universe’ (impersonal force, oracle, echo of a sutra) we are allowed to wander, accompanied by whirling depersonalised dancers in colour photography, to the promise of having identity’s burden lifted, to “step off to the side of the narrative” (82), the land of pure and promised absence, the empty green room.

Now that I think about it, I must have passed the orphaned ancestors many times and not noticed or read or thought about them. But the ancestors grow younger and one comes of an age to perceive, one passes through the “endless crashing moment” (5) of it and the drawing in of the nights seem to pertain not only to one's own little grove but the whole forest, the mithering mulch of it, the mere and entire terraqueous bauble. Text Messages arrived as a homage, a threnody, a casting forward of ourselves to our own moment of becoming hungry ghosts, a map for the “backdoor to the sky” (90) promise to not forget despite and because of our own condition of constant slippage, erosion, to not be perversely obsessive about breath and coursing platelets. Here we are, guided by the drones and alerts of the age, seeking not for the return to personhood but for the way, out, “until the sky is empty of thoughts” (95), drawn to the shapely void beyond tongue and symbol.