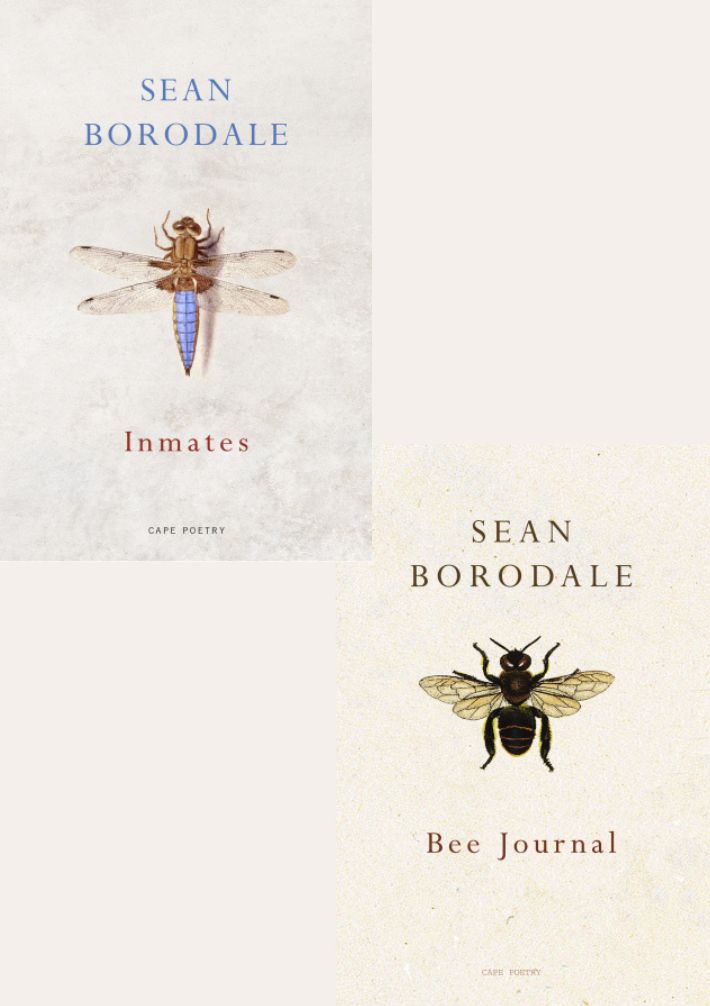

Inmates & Bee Journal

Sean Borodale has made a career out of writing about his interactions with insects and other little creatures in his home and life. Since 2012’s Bee Journal, which documents his acquisition of a hive of bees and his first steps into beekeeping, Borodale has had a laser-focus in writing about the world immediately around him. His next collection, Human Work (2015), turned the poet’s analytical lens to cookery and the inter-relation with those who cook, and Asylum (2018) presented poems with a geological aspect. With 2020’s Inmates, Borodale returns to the interaction of humans and insects, and in the eight years between the publication of Inmates and Bee Journal, there has been much change in the social and political life of how humans and animals interact. For example, since the devastating winter of 2013 in the USA, when bee populations dropped 23%, the US government has introduced two Farm Bills (2014 & 2018) which have dedicated between $20-34 million towards preservation of species that are largely affected by weather, disease, and adverse conditions. Looking at Inmates, and seeing what it discusses and how it differs from Bee Journal, sheds an interesting light on the way this poet sees our insect compatriots.

Obviously much can be made of the differences in subject matter, shown by the titles. Bee Journal is a catalogue of life as a novice beekeeper and frames itself as a calendar or almanac. It touches on many forms of the interaction between humans and insects, but there remains throughout a distance between narrator and narrated. The bees exist in their own home, the hive and all interactions take place in what is functionally neutral territory—Borodale cannot be in their home any more than they can be in his. As such, it presents an inter-dependency that insists on, and marks out as separate, the places of humans and insects.

From the very title, Inmates sets a profoundly different tone. The comparison between insect and prisoner isn’t directly referenced in any poem, but the pressure and impact of human life on insects is at the very core of the collection. The poems on display present a chafing relationship, where the very concept of human habitation, an intrusion into the natural order of the insect’s non-delineated world, is a prison that we force them into. However, it is clear from the poems that Borodale does not hold that the impact of humanity is purely negative. In the poem, ‘Dragonfly, Tracking, Re-tracking, Tracking’, Borodale posits that a dragonfly he sees in his garden would have led a very different life had it lived in a different area: “By another pond it may not have lived” (14). It is undeniable that we have imprisoned much of the world, but we have also protected certain environments through (admittedly scant) acts of preservation and conservation.

This broadly thematic difference between the two collections runs into the poems themselves. In Bee Journal’s opening poem, ‘24th May: Collecting the Bees’, the poet is arriving at a new place and taking on the responsibility of care for the bees. It is hopeful and full of life in a deep way. Contrasting that with the opening poem of Inmates, ‘Death Place of a Small Tortoiseshell Under its Food Source, the Nettle’, the discussion of the common British butterfly and how we interact with them is from the perspective of death: “As you / die secretly: / a damp mausoleum / of tattered wings” (1).

Inmates presents the meeting of the poet and insects at various points in their lives as they exist and live around each other. In keeping with this, much of the poetry observes the metamorphosis of insect species from egg to adult, whether in their infancy (‘Larvae, Disturbed’) or their changing of location throughout the day (‘Cobweb a.m. & Cobweb p.m.’). Yet there is a strand that permeates the entire collection that speaks of insects only in their death, or their discovery after death. Of the 49 poems in the collection, seven of them directly mention the death of the insect that is the subject of the poem.

Now, that is not to say that there’s not a deeply important discussion to be had around the mass extinction of animal species as a direct result of human intervention; but there seems to be a deep fascination, almost love with the death and dying of the insects for the poet. One would only wonder what the interaction between humans and the animal kingdom might look like if we did not so easily surround ourselves with a focus on the death of creatures. However, this is not to say that Borodale is only focused on death or dying. Several poems make it deeply clear that there is a strong fascination, or even love, that the poet holds for the creatures that fill the edges of his world. In ‘Bumble Bee’, the poet writes of the physicality of his subject:

The bee’s high shoulders are tufted

(8)

Its back, runged like a ladder;

Legs preening the body as it had stopped

Alternately, when Borodale considers the dragonfly in the poem ‘Dragonfly, Tracking, Re-Tracking, Tracking’, it is the innate and absolute connection between species and watery home:

In the burr of its head,

(14)

how long has it lived unseen in water,

To unpack its dry fire’s angled music?

While not the only time that colours and their influence come to the fore in the collection, in the poem ‘Peacock Butterfly Colour Wheel’, Borodale sees the butterfly as a crescendo of colours, all vivid and potent:

Fox fur and rouge; wall-flower red:

(18)

a furnace of heat:

dry red of fuller’s earth.

Taking these two strands together, what we can tell is that the poet has the knack to see something beautiful in every part of the life of the insect, and that is a refreshing and dynamic voice to be heard in the daily grind of animal neglect and abuse that permeates the media. As much as the presence of death might seem overwhelming in terms of the broader concepts of the collection, I think it telling that the longest poem, ‘Tick Hatchery’, is also the poem that deals most directly with the birthing of the ticks named in the title:

To examine,

(10-13)

to more closely microscope the waiting;

incubating light refracted over clusters

of eggs, unhatched, still

[...]

Somehow passionate,

egg-clusters panning her decay.

The transgression of blood:

Soil to grass to rabbit to cat to tick to tick-eggs

[...]

Her whole body,

its black battery full of deep red;

a congealing blood-sack,

five weeks old, six weeks old

As is clear in these lines, and echoed across the whole collection, Borodale refrains from painting the insects in too much fluff, something that is deeply alien to these creatures of dirt and dark spaces (e.g., ‘Maggots at the Back of a Cupboard’, ‘Pale Gestating Centipedes under Rotting Bark of Stacked Cherry Wood’). Instead, the blood and gristle of their lives is brought to the fore and discussed poetically. It is the success of the poems here that they make something arguably un-poetic poetic and do so in a way that makes them real to the readers. Even with the profundity of these species in our homes and gardens, most readers are unlikely to have engaged in such a close inspection of these creatures as Borodale does, and to truly embody the significance and worth of these insects is the best that the collection could hope for. That it achieves this gives hope that we can begin to evaluate our interactions more honestly with our domestic prisoners and that future collections might shine a greater, happier light on our insect compatriots.